- Home

- Helmut Walser Smith

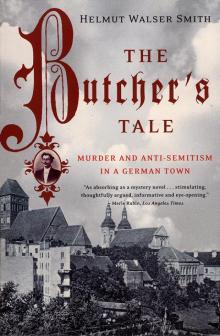

The Butcher's Tale

The Butcher's Tale Read online

THE BUTCHER’S TALE

For Meike

“Not until the hills are all flat …”

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue

1. MURDER AND RETRIBUTION

2. THE BUTCHER’S TALE AND OTHER STORIES

3. HISTORY

4. ACCUSATIONS

5. PERFORMING RITUAL MURDER

6. THE KILLER

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Illustrations

Index

More Praise for The Butcher’s Tale

Copyright

Acknowledgments

When you write, it’s a good idea to have a map of where you’re going. When I started this project, I had such a map. But somewhere along the line its bearings and markers ceased to make sense; that’s when the fun began, and that’s when I came to depend, more than ever, on the advice, help, and counsel of friends and colleagues.

Christhard Hoffmann first suggested that I pursue the story and convinced me to stay with it when prudence would have suggested otherwise. If it were not for him, this story would still be in my desk drawer. Christoph Nonn, who has written an important article on the Konitz case, offered valuable criticism at an early stage as well as insight and encouragement. Christoph is also writing a larger work on Konitz, and readers who are interested in how differently two historians can approach the same topic should consult his work as well.

In the initial stages of writing, the searching questions and criticisms of three friends—Margaret Lavinia Anderson, Michael Bess, and James Epstein—forced me to reconsider my assumptions and, in a sense, to start all over again, for which I am grateful. In the course of subsequent writing, I benefited enormously from the discussions about the case with friends and colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic, including Werner Bergmann, Chris Clark, Paul Freedman, Peter and Ruth Gay, Ulrich and Eva Herrmann, Pieter Judson (and his wonderful students at Swarthmore), Christian Jansen (who organized a forum at the Deutsche Historikertag in Aachen to present the work), Thomas Mergel, Jim Retallack, Marianne Sedlmeier (who more than feigned interest), Henry A. Turner, Siegfried Weichlein (who explained to me why Aristotle is important to the story), and Mieczyslaw Wojciechowski.

Discussions with friends at Vanderbilt, including Frank Wicslo, Margo Todd, Matt Ramsey, Rebecca Plant, José Medina (who saved me from a philosophical blunder), Jane Landers, Adrienne Lerner, Cheryl Hudson, Joel Harrington, Ed Harcourt, Katie Crawford, Beth Conklin, and Tycho de Boer, also shaped the manuscript. Bill Caffero, our medieval historian, patiently read, and reread, the chapter on the historical origins of ritual murder. Collectively, their suggestions have helped me a great deal.

I shamelessly assigned an early draft of this book to my undergraduate students in a class on the Holocaust and to my graduate students in a class on historical methods. Fortunately, my students did not shy from suggesting to their professor how he ought to improve his manuscript; one of them, Emily White, even took a red pen to my stylistic infelicities. At Vanderbilt, I have also received help in other ways. Mona Frederick, the executive director of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities, and her assistant, Sherry Willis, got me through the tribulations of a different book, thus allowing me time to work on this one. Lori Cohen, our administrative assistant in the history department, read chapters, charted graphs, and helped me in many other ways; as always, she has been wonderful to work with.

In the course of my research, I have also come to depend on the generosity of friends. In Berlin, Ulrike Baureithel and Christian Jansen have always helped me find a roof for short stays, and I am grateful to them for this and for our wonderful conversations. In the Polish city of Torun, Natalia Mielczarek, Lydia Smentek, and Andy Hess opened their home to me, and with their effusive hospitality helped me through the logistical difficulties of my research stay in Poland. In Chojnice (Konitz) itself, I was fortunate to have met Tomasz Myszka, who talked with me about the history of his hometown, showed me around, and eagerly read early drafts of the manuscript.

I am also grateful for the help of archivists and librarians in the United States, Germany, and Poland. The main holdings concerning the case are in the Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin-Dahlem, and I would like to thank Peter Letkemann and the staff of that archive for their help. I also found valuable documents in the Archiv Panstwowe in Bydgoszcz, in the Museum of Local History and Ethnography in Chojnice, the Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv in Potsdam, and in the Family History Library of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. The staffs of a number of libraries, including the University Library of NCU (Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun), the Staatsbibliothek Berlin, the Klau Library of the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, and the Jean and Alexander Heard Library at Vanderbilt, were immensely helpful. Special thanks to Jim Toplon and Marilyn Pilley, of Vanderbilt’s interlibrary loan office, who went out of their way to track down obscure pamphlets for me.

I am also happy to thank my friends at the Kim Dayani Center at Vanderbilt. Writing in the tenth century, the scribe Brother Leo of Novara complained that while three fingers write, the back is bent, the ribs sink into the stomach, and the whole body suffers. These days we have it easier, but the business of writing still requires long hours, in my case standing, before our keyboards. Moreover, poor brother Leo did not have Carmen Arab, Cassaundra Huskey, and Karen Dyer (and Karen’s smiling seniors and hugely funny Tuesday afternoon sculpting class), who watched out for me, joked with me, listened to my odd stories, endured my music, and in the course of things kept me, and my back, from coming further undone.

The book underwent significant transformations in the hands of Bob Weil and his assistant, Jason Baskin, two wonderful editors at W. W. Norton. Bob suggested substantial revisions, the kind that change the whole tone of books, while Jason poured his prodigious intelligence into my sentences and taught me, all over again, a lot about writing.

Finally, I thank my wife, Meike Werner, partner in all things that matter. For the past three years, she has listened to the stories of The Butcher’s Tale and read drafts of chapters; she has told me when it was not good enough and when it was, and she has shared her life, patience, and love with me.

THE BUTCHER’S TALE

Alleyway between the houes of Adolph Lewy and Gustav Hoffmann. The white crass on the left marks the door through which the Lewys allegedly emerged from their cellar with the torso of Ernst Winter.

Prologue

The greater part of historical and natural phenomena

are not simple, or not simple in the way we would like.

—PRIMO LEVI

When all is said and done, a single word,

“understanding,” is the beacon light of our studies

—MARC BLOCH

Amurder occurred on a Sunday night, March 11, 1900, in Konitz, a small town on the eastern reaches of the German Empire in what is now Poland. At first no one noticed that something was amiss. But then, two days later, the first body parts began to surface. They had been severed with a saw and sliced with a knife and then wrapped in packing paper and distributed, the upper torso here, the left arm there, throughout the town. The details of the murder unsettled the local population, but so too did the growing clamor of anti-Semitic accusations. A deafening chorus of voices charged the Jews with the murder.

The Jews slaughtered a Christian

Not far from the temple of Moses.

They sowed him in a sack

And brought him to the lake.

For them it was a blameless deed.1

The accusations, hurled by neighbor against neighbor, centered on an elaborate story, the butcher’s tale, w

hich drew from the ancient blood libel: that every year at Passover, Jews ritually slaughter Christian children and use their blood to bake matzo. The Jews had planned the ritual murder long in advance, ran the refrain; the Jews needed Christian blood, the people repeated. Many years later the expressionist writer Ernst Toller still remembered the shrill reverberation in his own hometown some fifty miles away. “The Jews in Konitz have slaughtered a Christian boy,” his schoolmates called after him, “and have baked the Matzo in blood.”2

Charges of ritual murder quickly led to violence, at first sporadic, then increasing in intensity, finally culminating in a series of major anti-Semitic riots. For the Jews of Konitz, their peaceful hometown had suddenly became a perilous place, “a war zone” where they “hardly dared leave their house.”3 Local officials were alarmed as well. Fearing that they could not control the riots, they called in the Prussian army to restore order and protect the Jews, who numbered just over three hundred men, women, and children in a town of ten thousand. As the army arrived in the region, the otherwise obedient West Prussian citizens stoned the troops, denouncing the men in spiked helmets as a “Jewish defense force.” “Had the soldiers not arrived,” a Jewish denizen recalled, “they would have torn us from our bed at night.”4

The anti-Semitic violence of Konitz in 1900, we now know, augured a calamity of altogether different proportions, in which the state, far from protecting Jews, pursued and nearly achieved their annihilation. Forty years after the rioters in Konitz shouted, “Beat the Jews to death,” a modern government, supported by a cast of willing executioners and ordinary men, did precisely that: first during the state-ordered, nationwide pogrom, Kristallnacht of November 9, 1938, in which shop windows were smashed, synagogues burned, and Jews beaten or killed; then with special killing units, the Einsatzgruppen and the police units, which during the war descended with unheard-of savagery on Jewish towns and villages in eastern Europe; and then, almost finally, with the industrial methods, at first primitive, later increasingly sophisticated, that made the extermination camps—Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek, and Auschwitz into—factories of death.

For the Germans of 1900, however, Auschwitz was literally unthinkable. The claim that within half a century their country would start two world wars and attempt to annihilate a people, some of whom were their neighbors, would surely have stretched their credulity and aroused their indignation. Their present, like ours, was contradictory and contingent marked as much by the possibilities of hopeful development as by the portentous signs of calamity. As Peter Gay reminds us about Jews and other Germans of this time, their future seemed “anything but a chamber of potential horrors.”5

By 1900, Germans had already left behind the stern authoritarianism of Otto von Bismarck, though they still venerated the Iron Chancellor, who had stepped down from the helm in 1890, and had passed away on his estate east of Hamburg in 1898. Bismarck’s departure opened the way for the more ambitious and unpredictable rule of Kaiser Wilhelm II, whom Bismarck once likened to a helium balloon that one constantly had to rein in. Flanked by his aristocratic entourage, the young kaiser increasingly overshadowed the mediocre chancellors who succeeded Bismarck. In the Wilhelmine era, as the period since 1890 came to be called, the kaiser watched over a system of “monarchical constitutionalism,” which gave modern form to Immanuel Kant’s famous characterization of Prussian politics: “Argue as much as you like and about whatever you like, but obey!” The crown controlled the army and foreign policy and safeguarded law and order at home. The chancellor answered to the kaiser, not to the German parliament, the Reichstag. Yet the Reichstag, elected by universal manhood suffrage, determined taxes and tariffs, and this meant that chancellors could not easily govern without it. Even though Germany was not a beacon of democracy, the existence of the Reichstag nevertheless ensured that Germans, and their politicians, practiced democracy, and, as the historian Margaret Lavinia Anderson has convincingly argued, they were getting better at it.6 The political party with the most delegates in the Reichstag, the Catholic Center, vigilantly guarded the constitution, while the most popular party, the Social Democrats, urged progressive reform, including women’s suffrage.

The effect of this democratization, however tentative, was palpable. By 1900, the power of feudal lords and imperious employers seemed on the wane, and authoritarian solutions to political deadlock, such as outlawing political parties and repealing universal suffrage, were no longer self-evidently in the offing. Instead, a new and modern civil code cemented the rights of citizens, including Jews, and progressive measures, such as voting booths and ballot envelopes, would soon ensure secrecy in elections. In other areas, too, Germany hardly appeared destined for a malignant future. After intermittent bouts of depression between 1873 and 1896, the economy had recovered and by 1900 seemed robust. By the turn of the century, Germans were everywhere involved in civic organizations: life-reform movements, beneficent societies, patriotic leagues, and recreational clubs. Often boisterous, sometimes chauvinistic, at times exclusive, these organizations nevertheless attested to the pervasiveness of the public sphere. The general education of the population also gave cause for optimism. In 1900, Germans counted among the most literate people in the world, with literacy rates in the range, of those found in the United States today. Their primary and secondary schools were widely admired if also feared because of their discipline—and their universities attracted students from all over Europe, including Russia, as well as from the United States. W. E. B. Du Bois, for example, welcomed the German universities as havens from the racist constraints in the educational system of his native country. Finally, German scientists distinguished themselves with great discoveries, honored in the first two decades of the twentieth century with more Nobel Prizes than most other major countries combined.7

“Past is prologue,” Antonio tells Sebastian in The Tempest: subsequent acts had yet to be written, and no one could know how events were to unfold.

Sensitive spirits, some historians rightly point out, already discerned something of an impending doom in those years. Admirers of the playwright Henrik Ibsen talked about “the demonic character of our age,” and critics, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche most pointedly among them, saw anti-Semitism as dyed deep into the fabric of what it meant to be German. The problem of anti-Semitism, its origins and persistence, also haunted the imagination of men like Aby Warburg, the brilliant art historian and scion of a wealthy Jewish banking family in Hamburg. Of the events of the times, it was the ritual-murder case in Konitz that drew his particular attention and inspired his reflections on the plight of Jews in an enlightened society intermittently punctured by the pointed awls of the atavistic.8

Warburg framed the problem of anti-Semitism in a way that has resonance for us as well. How do we understand prejudice, hatred, and violence in the context of modern societies, like our own, among people much like ourselves, among men and women who lived, not in dark times, but in an era when the balance of opinion was against the all-too-open expression of hatred?

This is not the only, or even the most popular, way of seeing the problem. In his immensely successful book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, Daniel J. Goldhagen described Germans who lived in the Third Reich as belonging to “a radically different culture” and the study of them as “disembarking on unknown shores.”9 The anti-Semitism of the Third Reich, he argued, was already anchored in the Second Reich, a society permeated by “eliminationist anti-Semitism.” Yet his critics rightly point out that in France during and after the Dreyfus affair, anti-Semitism was worse still; that in Russia murderous pogroms blotted the landscape with blood; and that in turn-of-the-century Germany, by contrast, political anti-Semitism had already ebbed, and other kinds of anti-Semitism were increasingly confined to the estuaries of social snobbery and the backwaters of the ideological fringe. World War I and the Weimar Republic changed things, to be sure. But in the final analysis Hitler came from the fringe, not the center, and it is from th

e ideas of this fringe, the radical nationalist milieu, that the coming disaster derived its ideological dynamic.

The Konitz case allows us to pursue a single, exemplary episode, cameo history, if you will: it neither tells us what all Christians in Germany thought about Jews nor explains whether Germany was already on a track to destruction. Yet the focus on the Konitz case reveals something that both Goldhagen and his critics overlook, and that something I would call here “process.”

Process is what makes latent anti-Semitism manifest, transforming private enmity and neighborly disputes into the blood-stained canvases of persecutory landscapes. In one context, the whispers of rumor and the wages of private malice fall on heedless ears; in another, they unleash a murderous dynamic. The preexistence of anti-Semitism, nationalism, or racism influences outcomes, but the outcome cannot be fully understood by a static measure of attitudes, anti-Semitic or otherwise. Looking at the process, we see historical forces converging: how local enmities become potent symbols resonating with larger antagonisms; how spiteful stories and tavern tales are elevated to public spectacle; and how these tales conform to a preexisting pattern of political and religious beliefs. We can also see how the accusations shift relations of power and support political agendas, and how people caught up in the resulting dynamic come to believe in the objective truth of their own lies.

The uprising in Konitz, the most severe outbreak of anti-Semitic violence in Wilhelmine Germany, allows us to see historical process at work.10 By training our sights on patterns of anti-Semitism at the local level, we can re-create, as Shulamit Volkov once put it, “the unique environment” in which anti-Semitism flourished.11 Save for scholars who have analyzed anti-Semitism in the metropolitan centers, historians have tended to eschew small-scale, high-resolution investigations.12 Instead, the vast and by now sophisticated scholarship on German anti-Semitism has typically focused either on the ideas of prominent anti-Semites, on the anti-Semitism of a particular group or institution, or on anti-Semitic politics.13 But important as such studies are, they do not show us how, among myriad influences, anti-Semitism became part of the warp and woof of everyday life. At the local level, we can see these things with greater precision than is often possible in a general study.14 And we can see the truth and the past, in the words of the Polish-American writer Eva Hoffmann, as “more striated, textured, and many-sided.”15

The Butcher's Tale

The Butcher's Tale